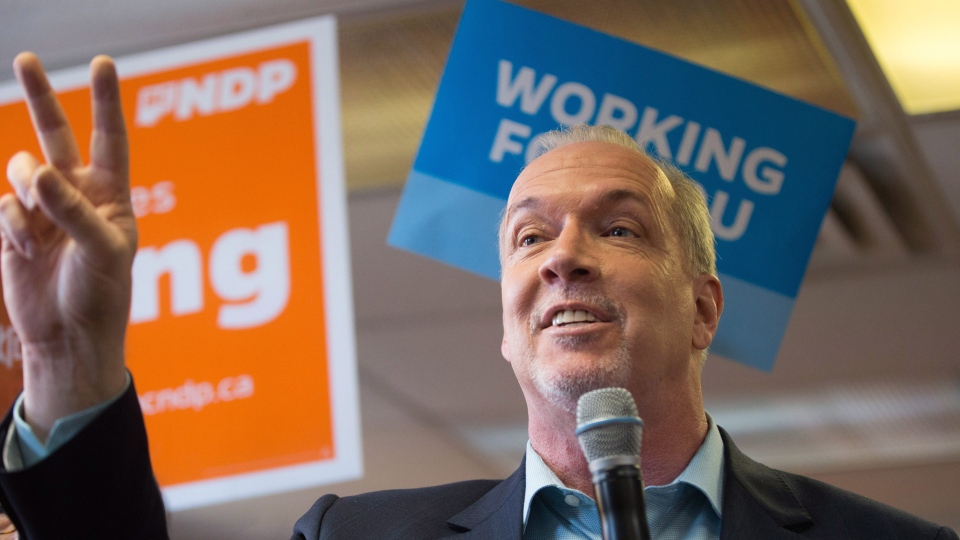

The new NDP government has put forward legislation intended to bring an end to the "Wild West" era of political donations in B.C.

A bill introduced Monday would ban donations from both corporations and unions and limit personal contributions to $1,200 a year – the second-lowest limit in Canada, according to the NDP.

"Today we're getting big money out of politics in British Columbia," Premier John Horgan told reporters. "This legislation will make sure that the previous election will be the last one dictated by the size of a party's finances."

Under the new rules, parties would also be barred from using previously collected corporate and union donations for future elections. The money could still be used for non-election expenses, such as office space and paying off debt.

Green Leader Andrew Weaver, whose party banned such donations a year ago, said he's hopeful the long-overdue bill will encourage the electorate to have more faith in the political system.

"The unparalleled influence of corporations and union donations has become a defining feature in our politics," Weaver said.

The NDP's legislation also outlaws donations from outside B.C., add new restrictions on fundraising events, and puts a cap on contributions to third-party election advertisers.

It fulfils one of the party's main campaign promises from the spring election, but the NDP came under fire in August for holding a $500-a-head fundraiser before reconvening the legislature.

Critics have also questioned whether the measures will be effective in removing big money from politics; Democracy Watch suggested the $1,200 personal contribution limit could still allow determined companies and unions to exert influence on the province's political parties.

"It will facilitate funneling of donations from businesses and unions through their executives and employees and their family members," co-founder Duff Conacher said in an email.

"In other words, it won't stop big money in B.C. politics, it will just hide it."

The only way to truly address the problem, according to Conacher, is by limiting individual donations to $100 annually as they do in Quebec.

During the transition away from corporate and union donations, the NDP has proposed an annual per-vote allowance for all parties, starting at $2.5 per vote in 2018 and gradually decreasing to $1.75 per vote in 2021. The system would be reviewed before the government decides whether to continue in 2022.

But the plan comes at a cost to B.C. residents, requiring more than $27 million over the next four years.

Critics lashed out at the premier for suddenly asking taxpayers to fund political parties, something he hadn't mentioned while on the election trail.

Liberal MLA Andrew Wilkinson, who represents Vancouver-Quilchena, said his party will not support the legislation.

"We're voting against the taxpayer subsidy because we don't think they should be on the hook for $28 million to hand out to political parties," he said.

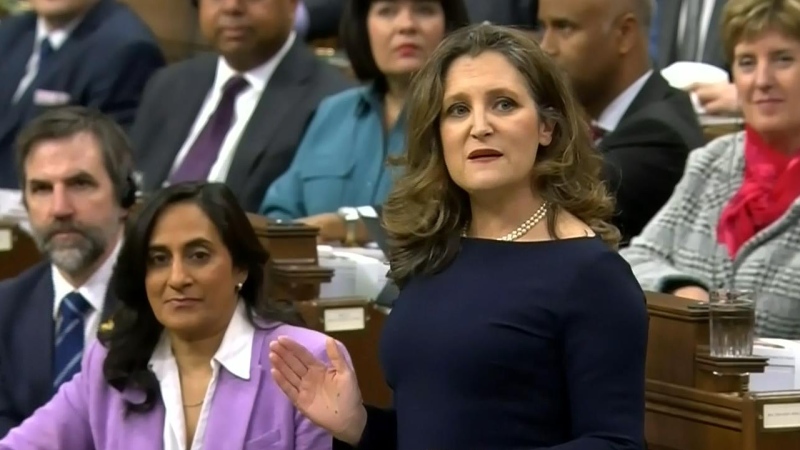

But Attorney General David Eby argued the previous system cost the public as well by letting unions and corporations fight for lower tax rates, and hold onto money that would have otherwise entered the public coffers.

"The current system is not free for British Columbians," Eby said.

"Union and corporate donations result in reduced income taxes for these unions and corporations that make the donations that cost the public millions of dollars."

The new rules would also reduce spending limits for candidates and parties by 25 per cent. Eby estimated the changes would reduce the overall amount of political donations by $65 million over the next four years.

In addition, the public will know ahead of time when party leaders or cabinet ministers attend fundraisers.

Campaign financing was a major issue during the last election, even drawing the attention of the New York Times, which published a story derisively dubbing B.C. the “Wild West” for its loose fundraising rules.

Union and corporate donations are already illegally federally and in Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia.

With a report from CTV Vancouver's Bhinder Sajan

Previous donations that aren't in line with new rules can't be used for future elections (but looks like party still gets to keep the $)

— CTV Bhinder Sajan (@BhinderSajan) September 18, 2017