Analysis: the system has long been a mainstay of Irish politics, but it has also been a vexed question for generations of political reformers

By Martin O'Donoghue, Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory

Addressing the Seanad on Leo Varadkar's resignation on March 20th, Senator Michael McDowell told the House that he believed 'Ireland was developing and maturing into a different kind of democracy'. He called on members to "consider whether application of a party whip in every matter really does add to Irish democracy" and whether members of a chamber with limited legislative power could vote "in accordance with their own individual preference".

McDowell is not alone in recently questioning the party whip system. The new Independent Ireland party promises not to operate a strict party whip system even in the Dáil as it "has stifled debate and diversity of opinion within our parliament for far too long".

Does this represent a sea change in how people want parliamentary democracy conducted in Ireland? Perhaps, but while the party whip system has long been a mainstay of Irish politics, it has actually remained a vexed question for advocates of political reform for generations.

Parnell's pledge

The term 'whip' has its origins in hunting parlance. Back in the 19th century, Irish Parliamentary Party leader Charles Stewart Parnell marshalled all his MPs to sign a pledge to "sit, act and vote" with the party. He sought to force the British parliament to focus attention on Ireland and discipline was prized.

But as the party's popularity waned, many pointed out the drawbacks to holding such a tight line. McDowell's grandfather, Eoin MacNeill, privately wrote to Maurice Moore in September 1916 that Irish MPs were "hopeless...because no able, honest man could sell his soul to his leaders in the way in which the Irish Party rank and filer is expected to do."

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Radio 1's Drivetime, historian Dr Conor Mulvagh on Charles Stewart Parnell's legacy

The independent Dáil?

As Laura Cahillane has shown, it was for this very reason that many feared what they perceived as the malign influence of party in the Westminster system when drafting the Irish Free State Constitution in 1922. Yet, it was not long before party dominance and the need to keep members in line became the norm in the Dáil too. Cumann na nGaedheal were not under pressure for votes and anti-Treatyites abstained until 1927, but thereafter, Fianna Fáil under Éamon De Valera brought discipline and obedience to the party leader which would have made Parnell proud.

'Democracy cannot work without parties'

Amid the constitutional debates of the 1930s, many commentators condemned the primacy of the whip as well as party machines more generally (and perceived civil service domination). Many public intellectuals of the day looked to the ideas of Catholic social thought to create a senate based on different sectors of society and free from party politics. These ideas were the wellspring for the vocational panels which still form the electoral basis of 43 of the 60 Seanad seats today.

In the early weeks of the chamber in 1938, even a senator representing a university constituency, Joseph Johnston (TCD) declared he stood "only on the understanding that those who sit on this bench are not bound by any Party Whips, and that we remain the captains of our souls". However, the electoral format for the Upper House adopted by De Valera helped to preserve a party stranglehold on the House's composition and, before long, its proceedings ran according to party lines.

Too strong a whip system left a TD a 'legislator in name but not in practice'

But did politicians believe in an alternative? In 1946, another senator and TCD professor, William Fearon queried why party politics were sometimes referenced "as if it were something not quite respectable". In the same debate, De Valera was clear: "when you come to examine it, you will find that democracy cannot work without parties, that people who have a particular point of view in common group themselves together - people who can work together in order to get a particular point of view accepted."

A looser whip?

Yet, in more recent decades, complaints have persisted. In 1980, John Bruton proposed Fine Gael reforms which would see the whip "loosened". In 2013, Eoghan Murphy made a similar proposal for votes on opposition amendments and non-money, writing that too strong a whip system left a TD a "legislator in name but not in practice". For Diarmaid Ferriter, the persistence of the whip in the 21st century remained a legacy of Parnell, leaving the parliament "still largely a galley of whipped voting slaves".

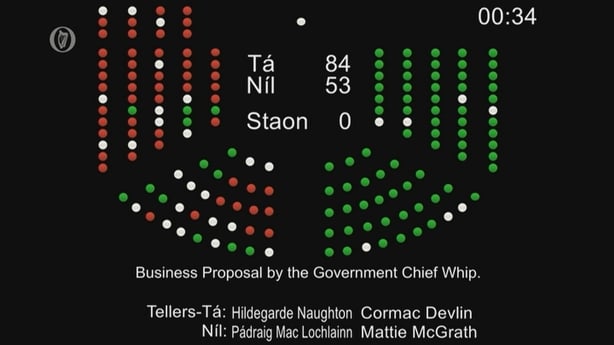

While pre-independence criticism spoke to disillusionment with Westminster and the hegemony of party, it may be argued that many recent criticisms have been underpinned by frustration at the dominance of government and the comparatively weaker position of parliament. The Fine Gael-Labour government (2011-2016) oversaw Oireachtas reforms, but lost a number of TDs who defied whip votes. Free votes remained rare and the deputies involved decried how strictly the whip was enforced in the Irish context.

However, the truth is that little changed even with the new politics of confidence and supply of 2016 to 2020. As David Kenny and Conor Casey showed, executive authority and the existing constitutional culture largely survived even when a government lacked a majority, something owed in part to the efficiency of Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil's respective whips. It remains to be seen if future reforms produce a different kind of democracy in relation to the functioning of parliament.

Follow RTÉ Brainstorm on WhatsApp and Instagram for more stories and updates

Dr Martin O'Donoghue is postdoctoral research fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory in Frankfurt. He is a former Irish Research Council awardee.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ